I used to think probability puzzles were mainly for math enthusiasts. The Monty Hall problem, in particular, seems designed to be counterintuitive. But the more time I spent analyzing SQL Server execution plans, the more familiar it became. It turns out Monty Hall and SQL Server share something important: both make you think you’re getting a fair choice when the odds were actually skewed before you began.

What’s Monty Hall again?

You’re on a game show. There are three doors. Behind one: a car. Behind the other two: goats. You pick a door. Monty, the host, opens one of the remaining doors to reveal a goat. He offers you a choice: stick with your original door or switch.

Your instinct says, “It’s 50/50 now.” But it’s not. The math says switching gives you a 2/3 chance of winning. Staying only gives you 1/3. It’s weird, but it’s true, they even proved it on MythBusters.

SQL Server does the same thing

The simplified version: SQL Server picks a door (an execution plan) based on what it knows at compile time. It makes a choice. Then it shows you the result: the plan it developed based on that initial information.

But the plan it picked might be based on incomplete information. Or a rare parameter. Or outdated statistics. SQL Server isn’t being deceptive. It’s optimizing based on the information available at that moment.

Let’s demo it.

Demo: Parameter Sniffing and Bad Optimizer Assumptions

Set up this demo in a test database.

-- Setup

CREATE DATABASE MontyDB

GO

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS dbo.MontyTest;

CREATE TABLE dbo.MontyTest (

Id INT IDENTITY PRIMARY KEY

,Category VARCHAR(20)

,SomeData CHAR(100)

);

-- Insert skewed data: 1 very common value, 2 rare values

INSERT INTO dbo.MontyTest (

Category

,SomeData

)

SELECT CASE

WHEN n <= 1000

THEN 'RareA'

WHEN n <= 2000

THEN 'RareB'

ELSE 'Common'

END

,REPLICATE('x', 100)

FROM (

SELECT TOP (100000) ROW_NUMBER() OVER (ORDER BY (SELECT NULL)) AS n

FROM sys.all_objects a

CROSS JOIN sys.all_objects b

) AS x;

-- (100000 rows affected)

-- Create index to make plan choices interesting

CREATE NONCLUSTERED INDEX IX_Monty_Category ON dbo.MontyTest (Category);You now have a skewed table: Common shows up ~97% of the time. SQL Server will act very differently depending on which value it sees first.

Step 1: Create a stored procedure to trigger plan reuse

-- Clean cache and create procedure

DBCC FREEPROCCACHE;

GO

DROP PROCEDURE IF EXISTS dbo.SniffMonty;

GO

CREATE PROCEDURE dbo.SniffMonty @Category VARCHAR(20)

AS

BEGIN

SET NOCOUNT ON;

SELECT * FROM dbo.MontyTest WHERE Category = @Category;

END;

GOStep 2: Run it with the rare value first

-- This execution generates the cached plan

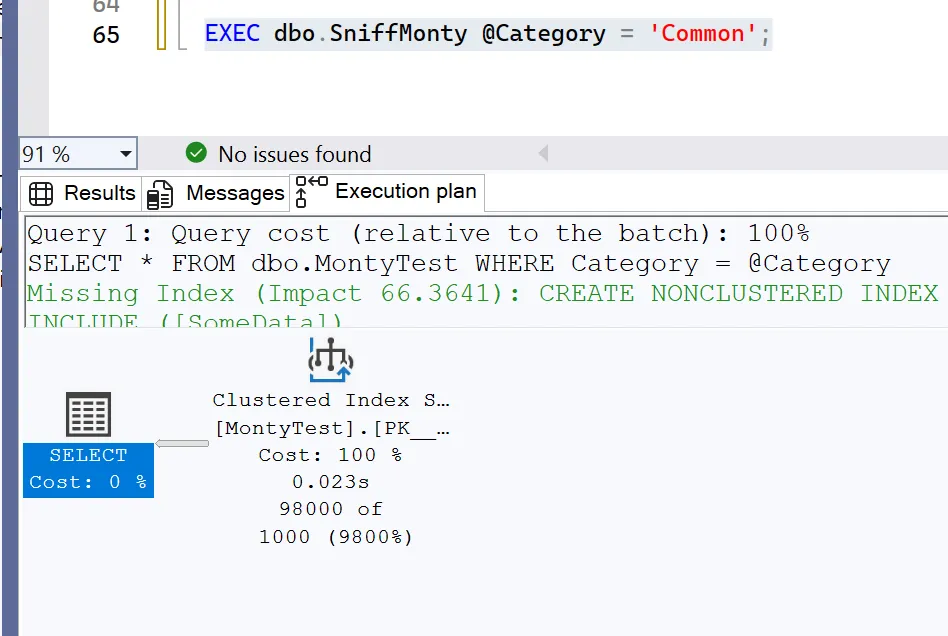

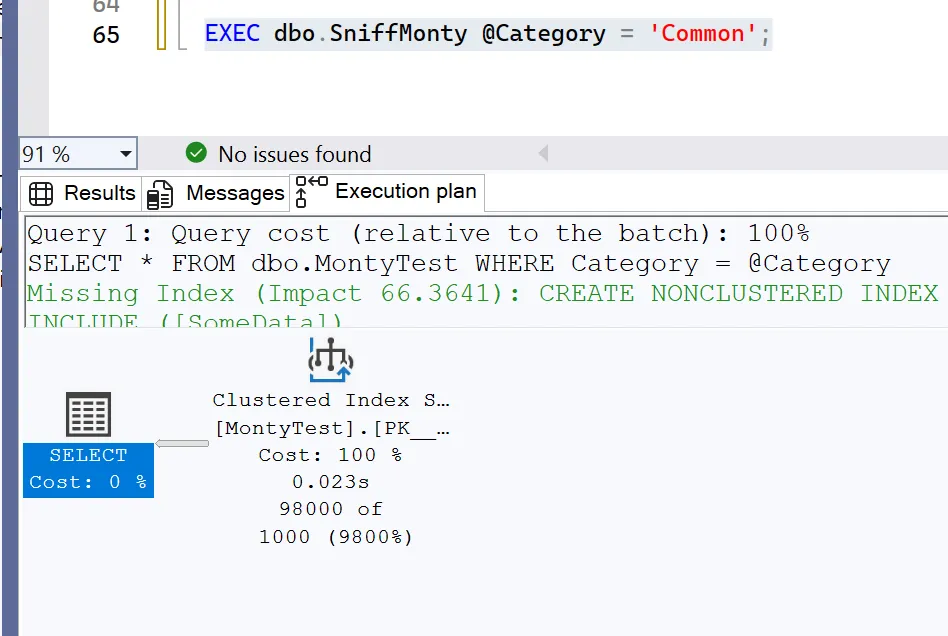

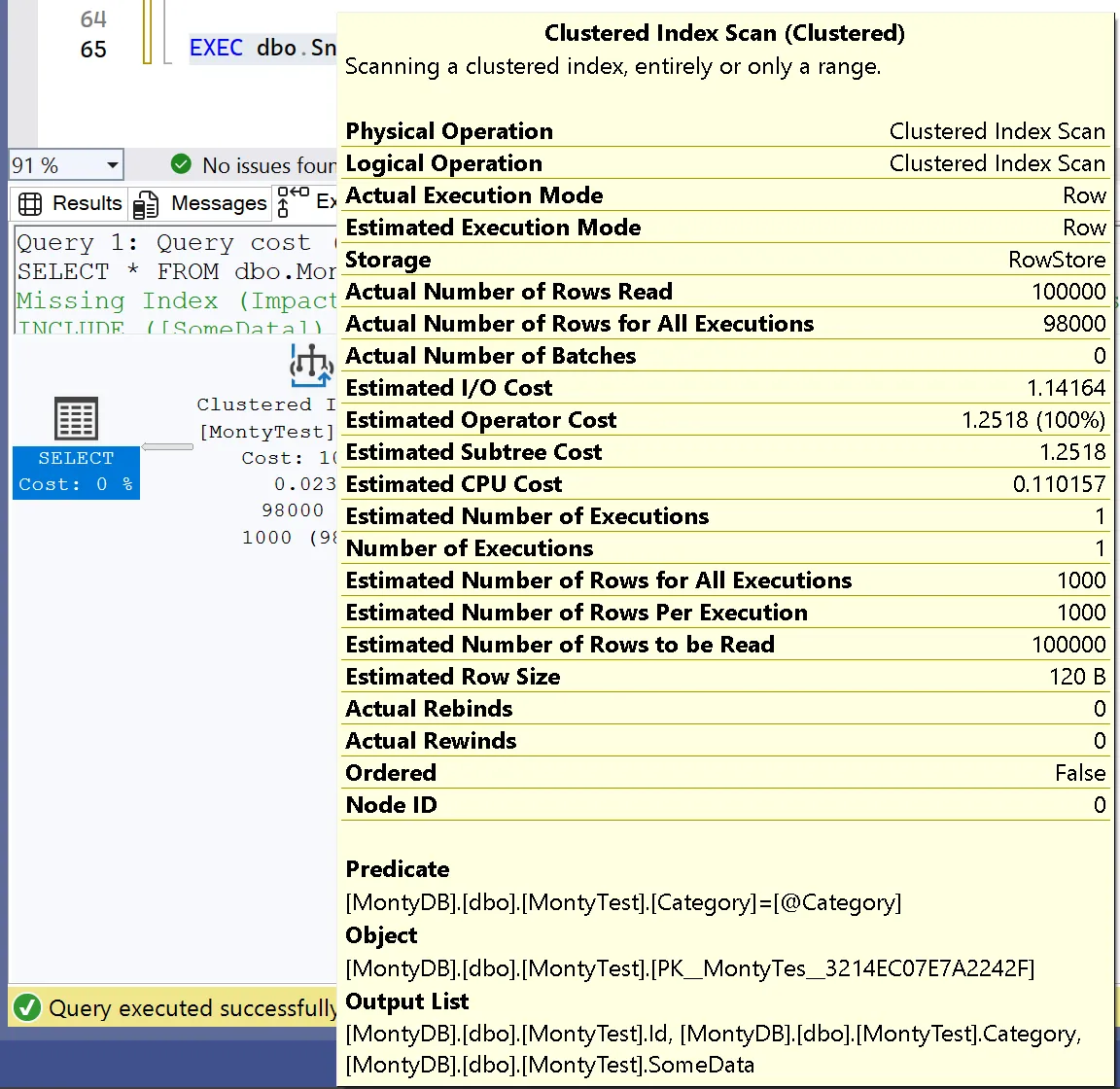

EXEC dbo.SniffMonty @Category = 'RareA';Now that a plan is cached for ‘RareA’, we’ll run it again but with ‘Common’. Below is the execution plan I received.

-- Run with common value — this is the “wrong” plan reused

EXEC dbo.SniffMonty @Category = 'Common';What’s happening is that SQL Server saw ‘RareA’ first, built a plan that works well for a small result set, and then continued using it. When we run it again with ‘Common’, it reuses that same plan, even though it now needs to scan almost the entire table. This results in nested loops performing thousands of key lookups, and performance degrades significantly. The plan isn’t incorrect, it’s based on an outdated assumption.

SQL Server generated an execution plan that estimated only 1,000 rows, when it actually needed to return 98,000 rows.

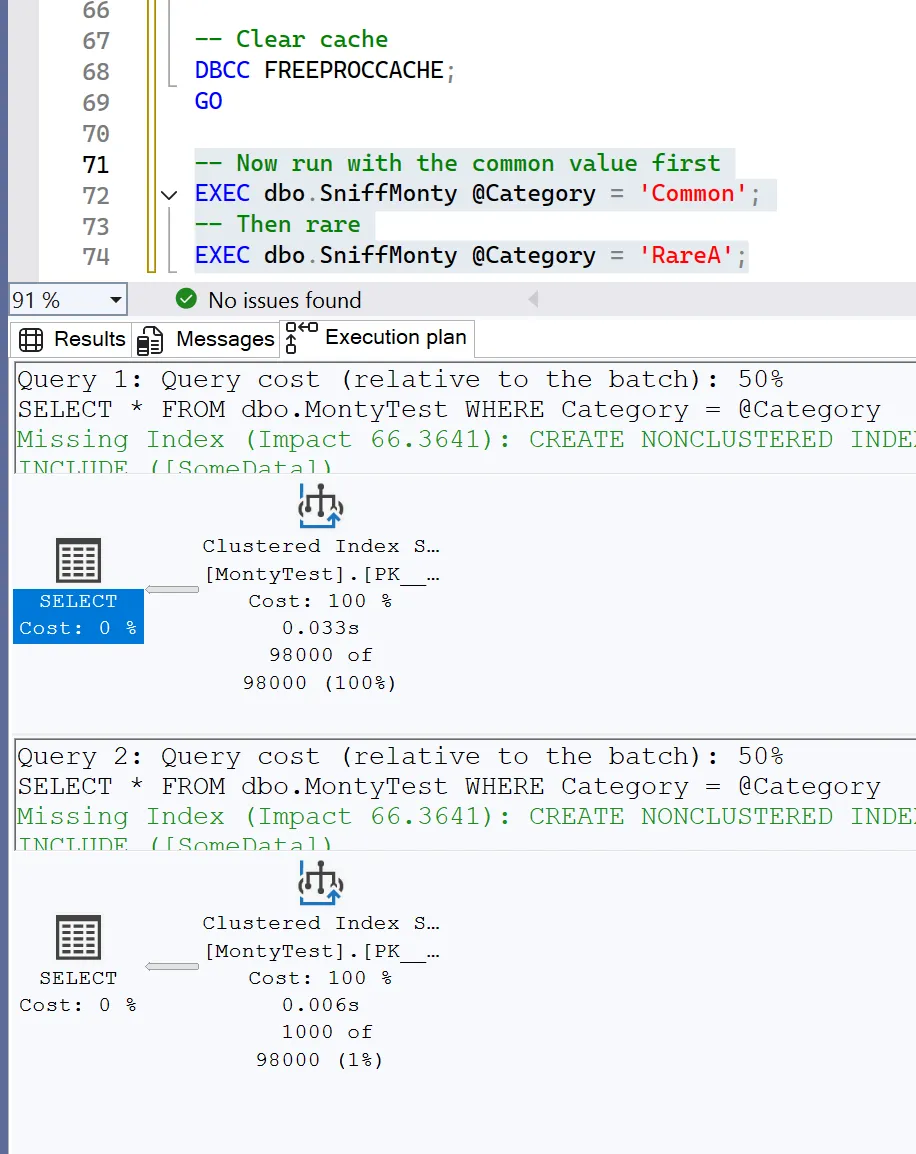

Step 3: Re-run it and reverse the order.

-- Clear cache

DBCC FREEPROCCACHE;

GO

-- Now run with the common value first

EXEC dbo.SniffMonty @Category = 'Common';

-- Then rare

EXEC dbo.SniffMonty @Category = 'RareA';

Now the plan is optimized for the common case. Running it with ‘RareA’ wastes resources reading way too much.

It’s not about right versus wrong. It’s about how SQL Server makes its decision before you know what parameters will be used.

The optimizer’s “door” isn’t random, it’s conditional. This is the Monty Hall connection. In the game show, Monty never opens the winning door. Up to this point I’ve been referring to this as luck, but it’s actually knowledge. Once he opens a goat door, the odds change.

In SQL Server, the optimizer sees parameter values, statistics, and cost estimates, then selects one execution plan. What it shows you isn’t a 50/50 choice. It’s based on what it considers most likely. And that cached assumption persists until you force it to change.

Solutions and Strategies

Sometimes we stick with the plan and get poor performance. There isn’t a perfect solution to this problem, but there are several strategies to mitigate it.

Use OPTION (RECOMPILE) to force a new plan for each execution. This approach avoids reusing a problematic plan, but it can be resource-intensive if the procedure is called frequently.

-- Force recompile per-execution

EXEC dbo.SniffMonty @Category = 'Common' WITH RECOMPILE;

EXEC dbo.SniffMonty @Category = 'RareA' WITH RECOMPILE;Other options:

- Use OPTION (OPTIMIZE FOR UNKNOWN) if you want SQL Server to make a generic plan.

- Use OPTIMIZE FOR (‘Common’) if you know most values will be skewed that way. This option does not scale well, however.

- Consider splitting procedures for hot vs cold values, or use dynamic SQL to avoid plan reuse where it hurts.

Key Takeaway: Question the First Plan

The optimizer’s job is to make an educated guess. Your job is to determine whether that guess is appropriate. Sometimes it isn’t. Sometimes it’s based on outdated statistics, parameter sniffing, or other factors.

When you encounter a poor execution plan, don’t assume it’s optimal for your use case. Ask what it was designed for. Ask whether the system made assumptions based on limited information. And when it does… consider switching approaches.